There is power in a first draft, but Hemingway was mostly right: first drafts are shit. Maybe it’s not that way for everyone, but for me and what seems like many people, first drafts are a start; you find your story in revision.

Revision is both the most gratifying and the most draining part of my writing life. It exhausts while it challenges, engaging my aesthetic and intellectual sensibilities simultaneously, my conscious and subconscious minds, and it leaves me so worn out that I no longer distinguish between the excitement of constantly thinking about and laboring over an essay, and the frustration of it. Revision is so essential that if I had to choose one line to describe the writing process, it would be: “writing is revision.” Maybe that’s why I love poet Robert Hass’s quote so much: “It’s hell writing and it’s hell not writing. The only tolerable state is having just written.” Exhausting or not, it still beats working in a cubicle.

Some people would disagree with the idea that writing is revision. There’s a popular notion that art is about inspiration, and the challenge of the artist is to capture a spontaneous outpouring as it happens, without spilling any of that molten magic while it’s hot. I don’t know where this idea came from. Maybe it stems from the human tendency to relax rather than work; maybe it’s as ancient as the Greeks. What I do know is that the idea can encourage laziness. By presenting the core mechanisms of creation as something extemporaneous rather than labor-intensive, revision comes to resemble a kind of ruination, a process of tinkering that dilutes the original potency of the spontaneous composition. The message is: “the less you mess with it the better.” I can’t speak for all disciplines, but for essay writers, I think that idea is damaging. When essayists do less, their essays contain less. Even the term “discipline” implies labor, practice.

The essays I like to read and try to write don’t spring to life as the proverbial lightning bolt delivered by magic or the gods. They accrue, developed through protracted effort to build, shape and layer. In tea terms: revision is the process of steeping to develop character. Those who resist it on the grounds that it lessens the raw life force of revelation not only fall prey to a clichéd, romantic notion of writing (the frenzied poet, scribbling fast enough to capture the words as they come), they often fail to fully tap all the meaning and power that their subjects and they as writers contain. Maybe that sounds smug, but in my experience, more work = better essay. For me, telling a story isn’t enough. Instead of an awesome anecdote, I want meaning, nuance, theme, dazzling sentences, interesting narrative architecture, little if any of which arrives when you first sit down to tap computer keys. If we could speak sentences as incredible as the ones we write, then writing would just be the act of transcribing words spoken into a digital recorder. I can’t think of any narrative nonfiction that I’ve read that resulted from that. Can Denis Johnson do that? Or Barry Hannah? Among his many accomplishments, Kerouac did us a disservice by making us think that writing was only about filling a scroll with speedy first takes. Maybe some writers think otherwise while the Adderall still has a grip on them.

We can learn a lot about revision from first impressions. People say you only get one chance to make one. That’s true, and sometimes you meet someone and immediately know, “Blowhard, don’t trust him,” or “Perv.” I always trust my gut. I also know that sometimes we misread people, so it’s wise to keep that first impression open to some amount of modification and allow in new information from further interactions. Meaning, as we get to know people, we broaden our initial perceptions and allow them to develop depth, even when depth contains the sort of contradictory information that is central to human nature. This is how revision operates.

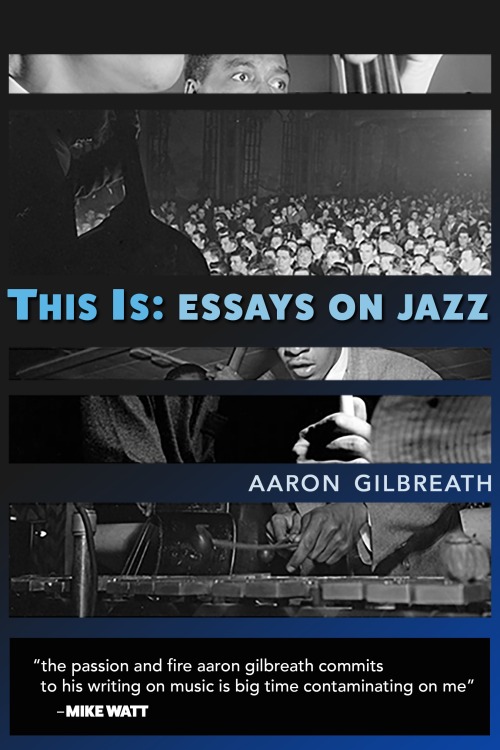

I might think I know what an essay is about when I start writing it, but I don’t really know. Oh, I think, this is about Googie architecture in my home town, or, This is about this one Miles Davis song where Miles pissed off Red Garland and had to play piano on the recording after Red stormed out of the studio. But that’s just one thread of the story, often the surface-level subject, what you might call the “ostensible subject,” which functions as a window into other component stories. Those other stories often reveal the essay’s theme: loss, regret, longing, failed hopes. They can also be the ones that readers connect to on an emotional or psychological level. More often, they’re the ones that address the question of meaning, or at least tries to chase meaning down. Ok, Googie, but what does it mean? In essays, meaning and theme are vital. I have yet to start an essay with either of them in mind. I find them through revision.

Revision takes me past my initial idea of what the essay is about. Once there, I explore the many facets of my story by going over and over and over it, plunging its depths. Ooh, what’s this here? And: Hey, that’s interesting. Never noticed that before, and I check it out. You see connections, see parallels, symbols, tangents and stories-within-stories. Revision is the playground where you can let your mind run free and discover not just things, but the things that are crucial to a literary essay. Instead of relaying information, and instead of just telling a compelling anecdote to get laughs or shock or entertain, spending time tinkering allows you to let go of narrative and your preconceptions long enough to see what it all really means. Which is to say, first impressions are important, but the more compelling portrait is a broader portrait, and that mostly emerges from revision.

To do this, you have to humble yourself: accept that you don’t know as much as you think you do, or as much as you would like to. If you explore your subject deeply enough, you’ll end up knowing a lot more than when you started. Readers will, too. That’s half of the fun. In the finished piece, your narrative voice might be confident, projecting the strength that assures readers that you’re taking them somewhere worthwhile and that you’re a knowledgeable, reliable guide. To get there, you have to stand before your subject and acknowledge your limits. You start out writing about X and Y, and you end up writing about who knows what. Without getting all New Agey, it’s the same thing we do when looking up at the full moon while camping and feeling like an inconsequential speck of dust on a rock in the vastness of space: there is so much we don’t know. I like to do the same with the story itself: whatever story I start with, I know that the bulk remains to be discovered. And so I revise.

To revise, you also have to be patient. You’re not going to finish that essay as quickly as you’d like. You might not finish it before your favorite lit mag’s reading period closes. You might not even finish it this summer. Good stuff takes time. That’s why barbecue cooked for a day over tended coals in a pit tastes a billion times better than that stuff people cook for a few hours over wood chips in a metal smoker. Go eat some ramen at Daikokuya in Los Angeles. You’re not going to tell the cooks that simmering their perfect porky broth for sixty hours was overkill.

I wish I had a system for revision. Granted, systems can be constraining and snuff out innovation, but they can also produce what scientists would call “reproducible results.” My only system is: drink tea, eat chocolate, and heed Harry Crews’ advice about keeping “your ass in the chair.” Sometimes I also chew on unlit cigarillos. I used to smoke and think I like the trace nicotine. Mostly it’s that, in lieu of specific revision strategies, Irely on that obsessive tea/chocolate/chewing nonsense to help me concentrate and keep me grounded during what is an inherently imprecise, ethereal, unscientific process.

In other words, I’m flailing.I drink tea and follow my gut. For all the formalities and “craft” stuff that I know, intuition is my guide. My chart: tell a good story; be insightful, probing but entertaining. Not dancing-in-short-shorts entertaining. Not ah-isn’t-that-clever, but entertaining in that I want to give readers a narrative that takes them somewhere deep, on a journey both through a story described and a landscape of ideas. How I extract that from the ether, or shape it from raw experience, is something I figure out differently each time. In that sense, revising always feels like I’m doing it for the first time every time. In another sense, the more I do it, the easier (“easier”) it gets. Maybe I’m getting more in touch with my intuition. Maybe I’ve become more willing to follow my gut and not second guess myself, or I’m becoming more reckless and willing to play around with narrative architecture and follow whims down the ideological rabbit holes and stop being such a cautious baby. Maybe I’m better able to recognize what it is I’m looking for: themes, symbols, metaphor, narrative.

What I’m left with each morning, then, are the basics: the need to go back into an essay and follow my instincts. I rearrange. I add and subtract. I pee in the beaker and see how that changes the flavor and coloration. There’s no big checklist of things to do or look for. It’s just “find the meaning,” “reveal the themes,” “have fun,” “tell a compelling story” and “cut out everything else.” I like what Rick Moody once said about writing: he tries to cut out all the parts that he as a reader would skip.

Even though this phrase sounds like one plucked from a teen goth message board, the “best advice on cutting” I’ve ever received came in the form of an offhand comment at dinner. A few fellow grad students and I were discussing revision, how much we loved or loathed it, ways we went about it. “I keep everything I cut in a separate document,” one person said. “That way I can always go back and retrieve it if I want to.” Then she admitted: “I never do.” Instead of using that separate document as a reservoir for retrievable overflow, she used it as a dump disguised as a storage shed. Knowing that all that material was there emboldened her cuts. She trimmed more daringly and frequently because she knew that whatever she cut hadn’t been erased, it had simply been moved to another page. If you need to think of revising partly as a form of moving things aside rather than eliminating, go for it. “Erasing” sounds final in a way that “moving offsite” does not, even when it’s just semantics. Tell yourself whatever you need to tell yourself to get the superfluous stuff out and find the keepers, because the truth remains: the absence of unnecessary text makes rooms for newer, better stuff, and that leaner arrangement allows the vital text to come more clearly into view.

Even though I’ve largely taught myself to write just by practicing for years, I learned other things in grad school, too. I attended a low-residency MFA program, so I didn’t spend as much time in workshop as I did alone at my computer. One of the things that brief workshop experience taught me, though, was how to identify and articulate what I was going on in an essay, the so-called mechanics of it. Another lesson proved useful during revision: the ability to read my work as if it were written by someone else.

One teacher at my grad program said that, after decades of writing and teaching, he could no longer read anything without editing it. Even if he wasn’t making editorial marks on the page, he was editing in his mind: trimming sentences, rearranging passages, formulating suggestions, rephrasing. If that seems obsessive, it is. It’s also a useful way to treat your own work. When you distance yourself emotionally from the words on the page and stop seeing them as the precious thing that you made yourself, you are able to see the story for what it is. Not the incredible object your brilliant brain made. Not the thing you labored over for weeks, the thing you ditched work to finish, or the thing that better get accepted by a magazine soon or you’re going to conclude that you suck at writing and go back to playing video games in basements in a cloud of bong smoke. No. It’s a story. It either works or it needs work to make it work. As a story separated from the act of creation and all its backstory, you can better see its machinery: what’s missing? What makes it drag? Should you slow this scene down to amplify the drama? How can you let readers see what this really means? Do readers really need to know all those details just because they happened as described? These are the sorts of constructive comments we make in workshop, or at least that we should be making when we’re not critiquing our classmates’ essays based on laziness, envy or malice. So after months of this constructive flailing, when do you know that a story is done?

There’s a famous anecdote in jazz involving Miles Davis and John Coltrane. When Coltrane was still playing in Miles’ first quintet – often called the “classic quintet” – and hadn’t yet started to gain control of his horn or the many sounds inside him, his solos could be erratic. Some were transcendent exaltations of emotion and architectural brilliance; others were uneven, stop/start affairs full of alternately radiant and apprehensive passages. You can hear this range on the records Milestones, Steamin’, Workin’ and Relaxin’. You can hear his vast improvements on Kind of Blue and ’Round About Midnight. Well at some point, Coltrane and Davis were playing or hanging out – I don’t remember the details – and Coltrane said something about not knowinghow to end a solo. Miles said, “Take the horn out your mouth.” Overly simplistic, but it’s still good advice. It reminds me of what the polymath Paul Valéry once said: “A poem is never finished, only abandoned.”

For those of us revising, maybe that’s a more useful guide that “finished.” Based on the responses of lit mag editors, my essays arerarely finished when I send one to them. Even the editors who accept my essays for publication often send comments and suggestions along with a requested revision. The process of editing together is a more collaborative version than most of us writers are used to doing alone, and it’s one so fruitful and invigorating that it makes me envy musicians collaborating in bands. Editor says I like X and Y, I think you should cut C and D, maybe better address the issues you raise in sections A and B. Then I revise. I can’t think of a single instance where I’ve revised something for an editor and the resulting essay wasn’t vastly improved. They’re always better. The experience has taught me two things: that (a) few finished stories are as finished as you think they are, and (b) what qualifies as “finished” is highly subjective, a matter of taste that varies reader to reader. You could go on revising forever. Sometimes you just have to take the horn out your mouth.

The essays that I quit revising and pronounce dead, I send to a folder called “the junk pile.” It’s like the oubliette in Labyrinth. If I feel that I’ve plumbed the depths of a subject deeply enough, that I’ve studied its angles and sculpted an essay that I would be so proud to let other people read that I’d be willing to take full responsibility for its strengths and weaknesses, then I take the horn out my mouth. No matter what you think of the idea that the Beats helped impart, that writing is a jazz solo, pure and unmodified, the fact of the matter is that not all jazz solos are entirely spontaneous. Once he quit using drugs and dedicated himself to his music, Coltrane practiced many of the parts of his best recorded solos. Other mid-century players did too. I’ll end there. I need to go chew on an unlit cigarillo.

* * *

I originally wrote this essay for Necessary Fiction.

Read Full Post »